Agricultural workers (Brockport, New York). Photo courtesy of Oak Orchard Health.

Summer usually signals the beginning of beach trips, long warmer days, and visits to the local farmer’s market, often brimming with fresh summer produce. Yet, by the time summer rolled around this year, the COVID-19 pandemic had already caused major disruptions to schools, employment, transportation, entertainment, and other industries. Agriculture, the mainstay of our food system, wasn’t spared.

When COVID-19 hit the United States, New York soon became the epicenter of the virus. Starting with a single confirmed case on March 1, the virus spread rapidly, to 408,181 confirmed cases and more than 25,000 confirmed deaths statewide at the time of this writing [on July 21, 2020].1

While COVID-19 has already put an end to many summer activities, it may be less apparent that it is also directly impacting our food supply and the workers who provide it. Our food supply is dependent on farm laborers —an essential workforce—who often risk their own safety and lives to provide the food we eat. Hired seasonally, agricultural workers are crucial during peak production periods. Working in fields, orchards, farms and canneries, they plant, cultivate, and process the crops.2 In contrast to states like California where the growing season is year-round, New York relies on the spring and summer season, when most crops are harvested.

The Workforce and Immediate Challenges

An estimated 2.4 million farmworkers fuel our agriculture industry. While some farmworkers have their permanent residence in the U.S., moving from one location to another during the season, other workers enter the United States through the H-2A program, which was created to allow foreign workers to work legally, on a temporary basis, for farmers who meet certain regulatory requirements. In 2019, approximately 258,000 visas were issued to H-2A guest workers.3 Still, more than half of all farmworkers in the United States are undocumented, and many live in mixed-status families and communities.4 While the characteristics of farmworkers vary by region, approximately 78% of farmworkers are Hispanic, and about 95% are of Mexican descent.2 The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic at the onset of the growing season, and in a shifting regulatory environment, exacerbated the challenges already faced by farmworkers.

Although agricultural workers have been deemed “essential workers” and “necessary infrastructure,” their living and working conditions make them uniquely vulnerable to illness, and compound longstanding language, cultural, financial and mobility barriers. During the season, many farmworkers live in dwellings with shared facilities, and may sleep in one room.4 Workers frequently travel to work in groups, and work side-by-side, and worksites may lack access to accessible hand-washing facilities with soap and water.

For farmworkers, the pandemic has added another level of fear and uncertainty; with no paid time off, workers simply can’t afford to get sick. And because few workers have health insurance, access and affordability remain a continuing challenge.5 While there remains no comprehensive testing or systematic reporting of positive COVID-19 cases among agricultural workers, clusters have been reported in Arizona, California, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Michigan, Missouri, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oregon, Tennessee, Texas and Washington – nearly everywhere that agricultural workers work and live.5

To learn more about the impact of COVID-19 on agricultural communities in our home state and around the country, we reached out to our colleagues at Finger Lakes Community Health (Penn Yan, NY) and Oak Orchard Health (Brockport, NY) and to the National Center for Farmworker Health (NCFH).

Testing, Education and Virtual Visits to Navigate a Crisis

Finger Lakes Community Health, in west-central New York State, was founded in 1989 as a free-standing migrant health center serving the region’s farmworkers. The health center was awarded a New Access Point grant in 2009 and became a federally qualified health center. In 2019, the health center operated nine locations and served approximately 29,000 people, around 30% of whom were farmworkers.

Mary Zelazny, Chief Executive Officer at Finger Lakes Community Health, recalled that in one county, just west of Syracuse, nineteen farmworkers at five different farms tested positive for COVID-19 and one died. Health center leadership recognized the pressing need for education about the pandemic, to curb the spread of misinformation and protect workers. Mary explained, “Farmworkers are at a huge disadvantage because they don’t have access to the news every day, they are working to feed their families, the news they get tends to not be local, because local news is in English.”

She went on to note that “At first we struggled with educating [farmworkers] and teaching them about social distancing and masks, but then some farmworkers got COVID-19.” The health center conducted multiple educational Zoom tele-halls in English and Spanish for farmers and farmworkers. The center’s medical director outlined safety practices and guidelines, available services, and answered questions. In addition to the tele-halls, Finger Lake’s team of community health workers continued their direct outreach to the farms. With farmers concerned that outreach and clinical teams might spread COVID-19 to their farms, the Finger Lakes team began making socially-distant visits to local farms, dropping off masks and hand sanitizer, as well as food and health and safety information, including how to properly wash masks.

The health center also initiated drive-up COVID-19 testing. Mary explained that, “The local public health departments had to come to us because no one else was testing. That is what we are here for, we are a community health center, tell us what you need and we are happy to do it.” An early adopter and leader in the field of telehealth, which it has offered since 2008, the health center has continued to offer virtual patient visits for routine health concerns. Finger Lakes was recently awarded grant funds through the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) COVID-19 Telehealth Program to add laptop computers, tablets, telehealth video equipment, remote monitoring equipment, and network upgrades to assist in screening, testing, and treatment for COVID-19 patients in eight counties. However, Mary cautioned that telehealth was a challenge for the more rural patients who don’t have consistent access to smartphones or broadband internet, and the health center has maintained some in-person medical and emergency dental visits throughout the pandemic.

Collaborations, and Mutual Trust

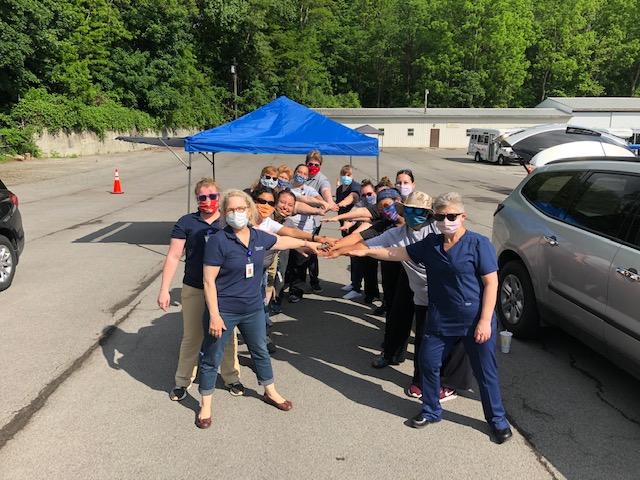

Situated in the northwestern most part of the state, Oak Orchard Health started as a migrant health project in 1966, and has since grown into a health network offering comprehensive, integrated health services at six locations including a mobile dental unit, and serving Monroe, Orleans, Wyoming, Steuben, Genesee, and surrounding counties. Commenting on the impact of the pandemic, Karen Watt, Vice Chair of the Oak Orchard Health Board of Directors and co-owner of Watt Farms in Albion, described a different atmosphere from years past, “There’s a little apprehension and trepidation for farmworkers coming into this area from other countries on the H2A program.”

Still, long-standing relationships across the community and the use of technology have helped ease some of the challenges. Navigators and enrollers work by phone to help patients get health coverage, with the bilingual team providing services in Spanish when required. Through a partnership with a local food distributor, the health center’s outreach team has arranged pick-up of food boxes for incoming farmworkers who were going to be quarantined. Sandra Rivera and Estella Sanchez Cacique, part of the outreach team, have provided drive-by drop-offs of masks, hand sanitizer, and disinfectant, along with health and safety information, at worker housing sites. The distancing restrictions required have been difficult for farmworkers. Sandra said, “I’ve known them for so long that they’re family. They want to tell me how their wife, kids, and mama are, and they’re not able to do that, it is so difficult for them. We have such a good relationship with the guys that I trust they will call us and let us know if they are feeling unwell and ask us what to do.”

Like Finger Lakes, Oak Orchard has also pivoted to telehealth, and has received COVID-19 FCC telehealth grant funds to help workers overcome barriers to care. Karen Watt mused, “What if the pandemic had happened before cellphones? Many of our farmworkers have cellphones – everyone is connected – it enables us to give so much more than would have been possible twenty years ago.”

A National Perspective and a Look ahead

Sylvia Partida, CEO of the National Center for Farmworker Health, explained that the challenges in New York were mirrored across the country. A key challenge for health centers was that many had to transition to telehealth becoming a primary way of delivering services, explaining that this occurred in the context of limited information about the types of technology and connectivity that agricultural workers might have access to. “I don’t think that the shift to telehealth is going to go away. We need to leverage technology and we have to help the farmworker community to fully engage in that type of service, for now and in the future. It’s critical.”

NCFH itself, long a champion of farmworkers through the training and technical assistance it provides to community and migrant health centers nationwide, has also sharpened its focus on the immediate challenges of COVID-19.

Together with other advocacy groups, NCFH issued a Statement on COVID-19 and the Risks to Farmworkers. NCFH also prepares a weekly summary, based on HRSA data, about Migrant Health Centers and COVID-19 tracking visits, site closures and testing capacity, and highlighting key health center issues. Resources for agricultural workers, employers and health centers are available in English and Spanish.

And in a unique collaboration with Justice for Migrant Women, the Hispanic Heritage Foundation and fashion designer Mario De La Torre, NCFH launched the Facemasks for Farmworkers campaign, which makes, procures and distributes face masks to agricultural workers, who like, other essential workers, have lacked adequate PPE. To date, the Campaign has distributed 9,000 masks made by volunteers, 7,000 made by designer Marco de la Torre, and is currently distributing 600,000 provided by an anonymous donor. The Campaign also secured 70,000 N95 Masks, 200,000 surgical mask and 1,000,000 nitrile gloves for distribution to community health center staff.

The Ag Worker Access Campaign , developed by NCFH in partnership with the National Association of Community Health Centers, has called on every health center grantee to increase by 15% each year, over the next five years, the number of agricultural workers served. With the pandemic underscoring the importance of care for the agricultural worker community, access remains a priority issue. The campaign, through the Ag Worker Campaign Task Force, is now focusing on building stronger partnerships with the agricultural industry and American Farm Bureau Federation, determining the types of resources needed by health centers in order to reach and provide more information about COVID-19 to farmworker communities, and developing broad distribution channels to make this information available.

Crisis situations often heighten access challenges, especially for vulnerable populations, and require both adaptability and innovation. Over the past few months, the COVID-19 pandemic has heightened the risks and challenges faced by our nation’s farmworkers. Fighting on the frontlines of this pandemic, community health centers continue to adjust and innovate to ensure the health and safety of the essential agriculture workers who keep food on our tables.

-Irene Bruce, Nela Abey and Feygele Jacobs, July 2020

1 Workbook: NYS-COVID19-Tracker. https://covid19tracker.health.ny.gov/views/NYS-COVID19-Tracker/NYSDOHCOVID-19Tracker-Map?%3Aembed=yes. Published July 21, 2020. Accessed July 21, 2020.

2 MHP Salud. Farmworkers in the United States. https://mhpsalud.org/who-we-serve/farmworkers-in-the-united-states. Accessed July 7, 2020.

3 Castillo M, Simnitt S. Farm Labor. United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/farm-economy/farm-labor. Published 2020. Accessed July 8.

4 Statement on COVID-19 and the Risks to Farmworkers. Resources on Novel Coronavirus COVID-19. http://www.ncfh.org/covid-19.html. Published 2020. Accessed July 8, 2020.

5 National Center for Farmworker Health. COVID-19 in Rural America: Impact on Farms & Agricultural Workers. http://www.ncfh.org/msaws-and-covid-19.html. Accessed July 13, 2020.

Staff at Finger Lakes Community Health. Photo courtesy of Finger Lakes Community Health

Photo courtesy of National Center for Farmworker Health

Photo courtesy of Oak Orchard Health